A game theory case against free speech absolutism

It isn't just politically disadvantageous for anyone who adheres to it - it actually *encourages* censorship.

Twitter has blocked a campaign video by North Carolina Lieutenant Governor candidate Rachel Hunt because of its “mention of abortion advocacy,” Alanna Vagianos reports for the Huffington Post. It’s easily the most controversial instance of Twitter censorship since the site banned Donald Trump a few years ago, squashing debate over what has long been one of the most contested political issues in the US.

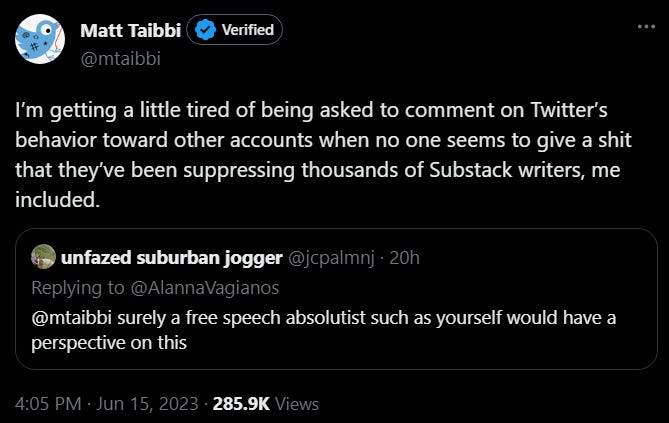

I doubt anyone will be surprised, at this point, to learn that our self-appointed “Free Speech Champions” have had nothing to say about this. Glenn Greenwald, for example — who openly ridiculed concerns about Elon Musk’s takeover and obliviously praised its “potential…restoration of free discourse” as “exciting and encouraging” — has exclusively focused on Tucker Carlson’s ongoing litigation with Fox News. Meanwhile, when Matt Taibbi was asked for comment, this was his response:

Taibbi’s comment is particularly ironic since he is just repeating a complaint that the left has been making for months: that his Twitter Files reporting was little more than a demand for the left to care about censorship of the right even as it conspicuously ignored Twitter censorship of the left.

It’s ironic, but it also illuminates a basic sociological flaw in liberal free speech politics. In order to maintain free speech, liberalism proposes a norm of reciprocity: it’s in everyone’s interest to defend free speech for their enemies so that their enemies will defend free speech for them. But in practice, no one actually adheres to this rule, and a major reason is the one given by Taibbi: everyone believes that the other side isn’t keeping up their end of the bargain, which means that they don’t need to, either.

It’s time for some game theory

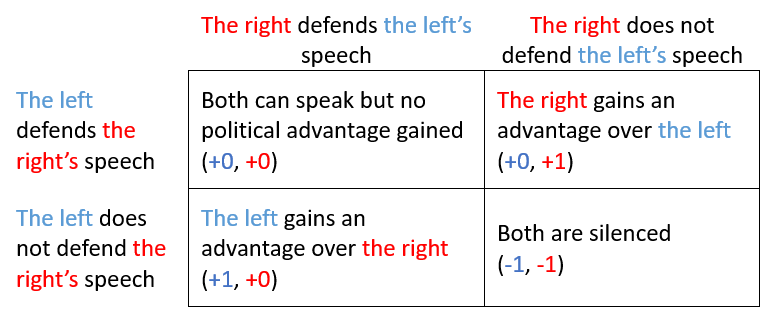

There are plenty of radical left critiques of free speech liberalism, of course, but one of the most damning objections can be explained as a matter of game theory. We can begin by constructing a so-called “payoff matrix” which demonstrates the basic decisions that the left and right can make about free speech, and their outcomes:

Readers who have even a passing familiarity with game theory should immediately recognize this table as sketching out a variation on the famous Prisoner’s Dilemma. For both sides, the best possible outcome is if your opponent defends your speech while you betray them. If both sides choose to pursue this outcome, however, then they could hypothetically get the worst of both worlds: a free speech regime where neither gains a real advantage and both are routinely silenced. Therefore, liberals insist, we should both agree to pursue the first outcome: we defend each other’s speech, and thus while no one gains a political advantage this way, no one gets censored, either.

Usually this is where the liberal analysis ends — but it is not, however, where game theory’s analysis ends. All we have done so far is diagram a single scenario where the left and the right have conflicting free speech interests. But in real life, of course, free speech isn’t a one-and-done decision: we are faced with questions about how to handle it every day, over and over again. This creates what game theory calls an Iterated Prisoner’s Dilemma, which creates new problems that the liberal solution doesn’t address.

To appreciate the problem, let’s “score” the IPD based on the following rule: if both sides defend free speech, no one gets an advantage (0 points). If one side defends the other’s free speech but is betrayed, the other side gains a point. And if both sides refuse to defend the speech of the other, both sides lose a point. So the payoff matrix looks like this:

At first, you might think that the best strategy would be for both sides to just stick to free speech liberalism: that way no matter how many rounds of this you play both sides end with zero points. But what if the left decides to cheat one round and refuses to defend the right’s speech even though the right defended its speech? In that case, if does not make sense to maintain the truce, because that will leave the left with a permanent one-point advantage. In that case, the rational thing is for the right to retaliate one time, evening the score, and then return to the liberal strategy of liberal free speech. This is what game theory calls a tit-for-tat strategy: if your rival keeps the truce then you do too, and if your rival betrays you then you get to betray them back.

So already we can see that so-called “free speech absolutism” only makes sense if your opponent never cheats. If your political opponent refuses to defend your speech, then the rational choice is for you to retaliate one time. This nullifies any advantage they gained over you and it takes away any incentive they have to continue cheating. While it may seem counterintuitive, this is just a matter of logic: if you want to defend free speech, sometimes the best thing you can do is support censorship!

Another failure of liberal proceduralism

One could argue that Matt Taibbi, in his tweet, is intuitively expressing this basic point of logic. He believes that left critics have not been reciprocating in the liberal free speech truth, and so he’s retaliating by refusing to speak out against Twitter’s censorship of abortion advocacy. Generously, one could even suppose that this is a deliberate tit-for-tat calculation on his part, and that moving forward after this he will return to a principled free speech position.

But that raises another problem: is Matt actually engaged in one-time retaliation here? Because his critics on the left, of course, would say that they were retaliating for his refusal to defend their speech in his Twitter Files reporting. If that is true, then Matt is not doing tit-for-tat; he is just repeatedly cheating the truce while spinning each instance as one-time justified retaliation. And in that case, the left would be fools to return to a free speech norm that the right simply isn’t honoring.

Unfortunately for free speech liberalism, when we try to distinguish cheating from justified tit-for-tat retaliation, it only becomes clearer that this question is itself inherently political. A rational approach to free speech norm setting would require everyone to review a long series of free speech controversies and come to a consensus about whether both sides complied or not; it doesn’t let you consider single episodes in a vacuum. But there is obviously never anything even remotely resembling a consensus about who has been playing along with the free speech truce and who has not.

And this means that liberalism’s free speech norm has utterly failed in the specific thing it set out to do: provide us with a neutral procedure for navigating political controversies. It does not even do this in a way that avoids censorship, because the principle of reciprocity demands retaliatory censorship if we want any free speech at all. Even worse, it creates a new procedural pretext for censoring things that you substantively disagree with: you can just say that you are doing so as a matter of retaliation, not because you actually disagree with them. (Is Taibbi refusing to condemn Twitter’s censorship of Hunt in retaliation against the left, or because he substantively opposes her politics? We’ll never know!)

If you have seen the endless arguments in the discourse over whether the left or right is more censorious, or if you have seen the extremely common phenomenon of politically selective outrage over censorship, then you probably already have an intuitive appreciation for the critique I am getting at; here, I’ve just used game theory in an attempt to lay it out formally. Free speech isn’t a prisoner’s dilemma — it’s an iterative prisoner’s dilemma, which means that a “cooperative strategy” of free speech absolutism would be politically suicidal and counterproductive for free speech itself. But because we have imperfect information — since we cannot, that is, arrive at any kind of real consensus over how previous iterations of the game played out — an iterative prisoner’s dilemma analysis of free speech doesn’t really work, either. That doesn’t mean that it’s impossible to try to build a society that maximizes everyone’s ability to debate ideas and expresses themselves; but it does mean that liberal norm-setting is a colossally stupid way to do it.