Richard Hanania doesn't understand economics

In his latest misunderstanding of science, Hanania misses economics' crises of legitimacy.

Today in The New York Review of Books, Trevor Jackson recounted what may very well be the most catastrophic Microsoft Excel error in history:

In 2010 Reinhart and Rogoff published a short essay in the American Economic Review called “Growth in a Time of Debt.” It purported to show that any time a country’s public debt exceeded 90 percent of its GDP, growth sharply declined. This claim was widely cited by politicians and accepted as a factual justification for austerity, to the extent that Paul Krugman thought it “may have had more immediate influence on public debate than any previous paper in the history of economics.” In 2013 a then Ph.D. student (now an economist at John Jay College) named Thomas Herndon attempted to replicate their study and found grievous errors in their data.

Mathematicians Jon Borwein and David H. Bailey elaborate:

The most serious was that, in their Excel spreadsheet, Reinhart and Rogoff had not selected the entire row when averaging growth figures: they omitted data from Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada and Denmark.

In other words, they had accidentally only included 15 of the 20 countries under analysis in their key calculation.

When that error was corrected, the “0.1% decline” data became a 2.2% average increase in economic growth.

This, Borwein and Bailey continue, was more than just a one-off mistake. Modern economics often relies on enormous volumes of data and elaborate computational analysis that can be difficult to replicate without going well beyond ordinary standards of documentation. As a political matter this is dangerous for reasons given: even minor errors in economic research can have unusually widespread human consequences.

As a scientific matter, meanwhile, the replication crisis facing economics is just one of many that call into question the legitimacy of the discipline. These are not mere errors or disproven hypotheses that science, as a self-correcting process, can be expected to run into from time to time; they are problems of the discipline’s compliance with science itself.

***

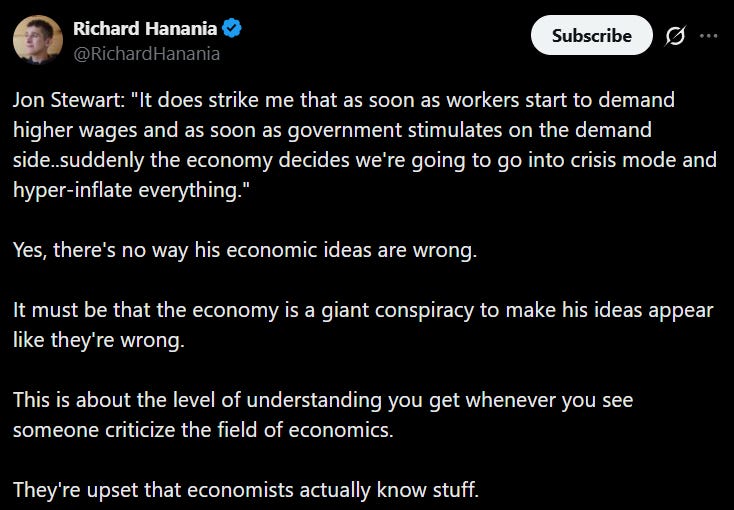

I found myself thinking about the Reinhart/Rogoff affair earlier today when I read another article, this one by liberalism’s favorite race scientist, Richard Hanania.1 In it, Hanania complains that Jon Stewart recently made a number of comments that treat economics not as a science, but as a political project. You can read the article if you like, but you can really get the gist of it here:

Here, Hanania thinks economics proves that if you do things to help workers like raise taxes and demand higher raises from the rich, the rich will inevitably respond by raising prices, which will get you inflation. Thus he ridicules Stewart for refusing to accept this supposedly scientific finding and suggesting that the rich did not have to do this.

There is a trivial and mostly semantic sense in which Hanania has a point: insofar as we use “economics” to mean an abstract field of scientific inquiry, it does not make sense to accuse it of having an agenda.

But that is not how Stewart is using the term, of course. Clearly, he is just using the term metonymically to refer to the discipline of economics as presently embodied in its practices, institutions, and body of work. And in that sense, it is perfectly legitimate to argue that really existing economics functions today more like a political project than a scientific project. To use an analogy that might hit close to home for Hanania, we can use the term “economics” like most people use the term “race science”: to refer to something that postures as a science, but that has historically had far more to do with politics and pseudoscience than anything resembling an epistemelogically neutral and self-correcting research program.

Here, this critique seems warranted on two grounds.

First, note that Hanania does not specify what claim of economics Stewart is at odds with. This is because what he seems to have in mind is “the law of supply and demand,” which tells us that capitalists will respond to increased demand by raising prices. Supply and demand is such a foundational point of contemporary economics that it is understandable Hanania wouldn’t even bother to specify it; to reject it would, in a significant sense, compromise much of the really existing discipline.

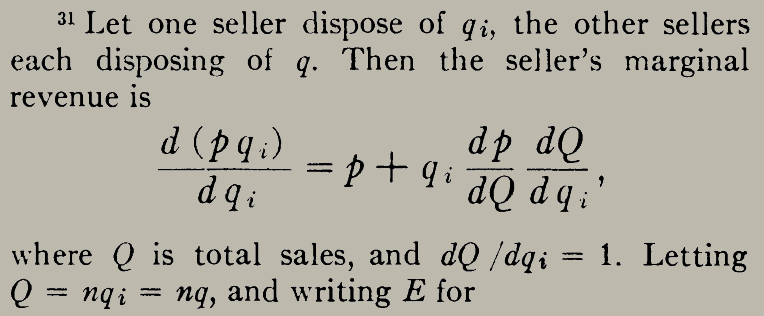

And yet from an actually scientific perspective, it seems that this is exactly what we must do. As Steve Keen observes in his Debunking Economics, the law of supply-and-demand has been formally disproven — and not even by some radical Marxist or heterodox economist, but by Nobel Prize winner and Chicago School icon George Stigler:

In his paper “Perfect competition, historically contemplated”, Stigler applied one of the most basic rules of mathematics, the “Chain Rule,” to show that the slope of the demand curve facing the competitive firm was exactly the same as the slope of the market demand curve...if you have [studied economics], this should shock you: a central tenet of your introductory “education” in economics is obviously false, and has been known to be so since at least 1957.

This is why Keen, who himself is an economist, titled his book Debunking Economics. That supply and demand has remained a foundational “law” of economics three quarters of a century after it was formally annihilated tells us that something isn’t just wrong with the the law — there is a real problem with the entire discipline. This is true even if subsequent work built on supply and demand has had practical value. Prescientific and even pseudoscientific work often seems to have practical value, but since it does not confirm to the basic rigors of falsification and internal coherency, we cannot call it scientific.

That said, there is also a second and simpler objection to Hanania’s critique, which is that the law of supply and demand only even hypothetically describes what is going on in conditions of perfect competition. In capitalism, this means that capitalists get to set the price, which gives them the luxury of offsetting payroll costs and taxes with markups.

But socialists have a counterproposal: instead of letting capitalists set prices, you can let workers set them through the arm of the democratic state. When you do this, no capitalist is in a position to game the system and pass expenses on to their employees.

Jon Stewart is a liberal, of course; he is not proposing nationalization. But insofar as socialism is a political solution to this problem, he is correct to politicize the fact that we let capitalists set prices however they like. And insofar as Hanania thinks that economics gives the state no way to raise wages or tax the rich, it is he who misunderstands the science.

Refer enough friends to this site and you can read paywalled content for free!

And if you liked this post, why not share it?