Why should the rich have privacy rights?

No sympathy for the Coldplay Couple!

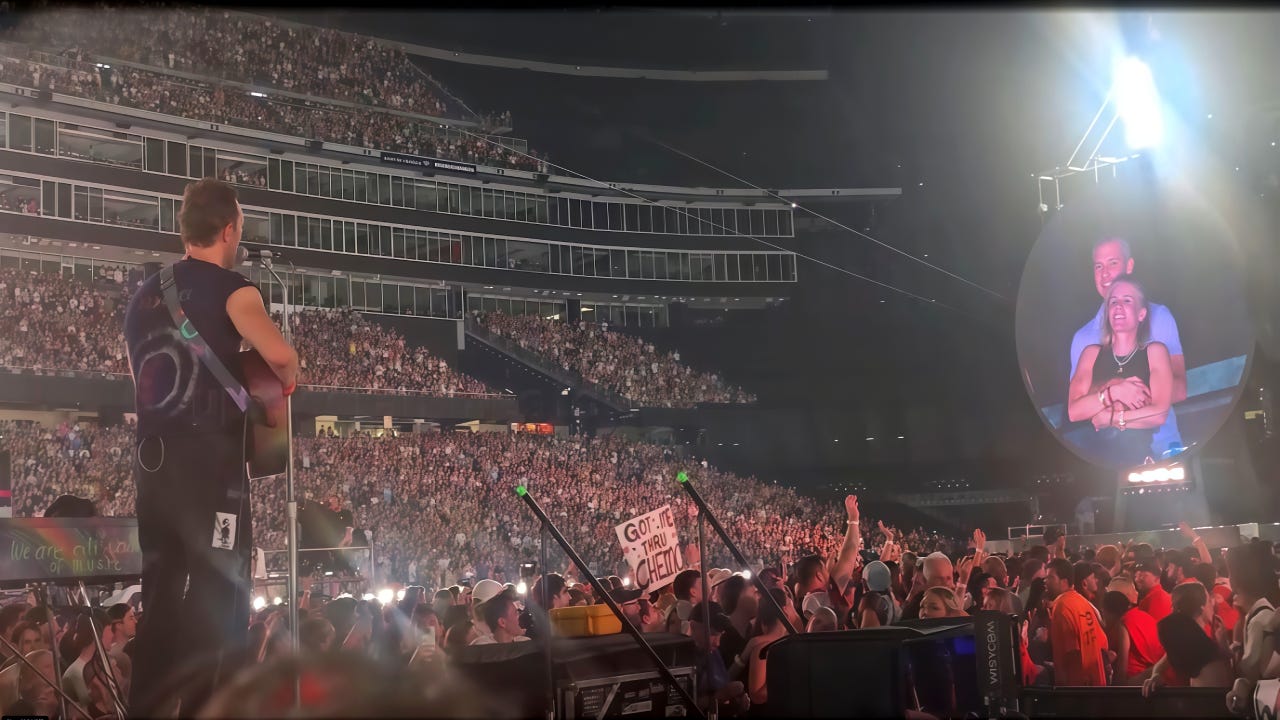

Liberal privacy rights ran into a hilarious crisis yesterday — and of all places, at a Coldplay concert. That’s where tech CEO Andrew Byron got caught on the kiss cam embracing a woman who was clearly not his wife; evidently she is one of his employees. “Either they’re having an affair, or they’re just very shy!” Coldplay frontman Chris Martin joked to …