On Trump's Greenland gambit

Escalating tensions between the US and Europe can create important opportunities for the left.

It’s an extraordinarily bad sign that we hear so little about climate change these days, even on the radical left. The obvious explanation is that our news has been dominated by Trump’s sabre-rattling over Greenland on one hand, and ICE’s escalating war on Americans on the other — but both of these problems are directly downstream from the climate. Greenland has strategic value to the United States precisely because it positions us to exploit fossil fuel reserves that will become accessible as the polar ice begins to melt; meanwhile, about half of Latin American immigrants into the US are coming from its so-called “dry corridor” (El Corredor Seco). As climate change intensifies, the US’s crackdown on immigration is likely to become even more draconian, and its efforts to access polar fossil fuel more frantic and combative.

In that light it’s probably worth questioning the liberal-left conventional wisdom that tensions with Europe and ICE crackdowns are both exclusively Trump problems. Trump may be ahead of the curve on both, but climate change means that we were always likely to deal with both problems sooner or later.

And this, in turn, is why the left needs to look much further than simply defeating Trump if it wants to turn back the tide of domestic crackdowns and international conflict. We even, in fact, have to look further than the usual ambitions of electing socialist officials to govern the United States. Climate change is a problem that requires global cooperation on a scale that just isn’t plausible without a central democratic body with the authority to redirect global resources and implement global projects as needed. You need to channel trillions of dollars to the Global South and you need to transform the entire fossil-fuel-based energy infrastructure that human civilization has relied upon for thousands of years. You need global socialist governance.

Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney, speaking at Davos earlier this week, delivered a remarkable speech:

We knew the story of the international rules-based order was partially false. That the strongest would exempt themselves when convenient. That trade rules were enforced asymmetrically. And we knew that international law applied with varying rigour depending on the identity of the accused or the victim. This fiction was useful. And American hegemony, in particular, helped provide public goods: open sea lanes, a stable financial system, collective security and support for frameworks for resolving disputes. So, we placed the sign in the window. We participated in the rituals. And we largely avoided calling out the gaps between rhetoric and reality.

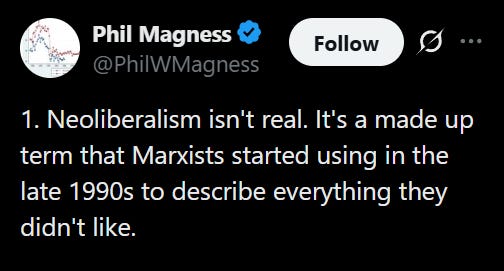

It has been gratifying to see the leader of a Western nation say openly what the left has been arguing for years, particularly given that just a few years ago it was still fashionable for liberal pundits and intellectuals to deny that neoliberalism even exists.1 And leftists have also celebrated the potential implications: Ben Norton, for example, writes that “it would be objectively good for the majority of the world population (which is in the Global South) if the Western imperial alliance broke apart”.

But here, again, climate change complicates matters. A multipolar world could conceivably curb the domination of global affairs by the United States, but it may also make it harder to achieve the kind of international cooperation the fight against climate change needs. Competition over polar fossil fuel reserves illustrates this problem vividly. In a world dominated by US interests, leaving those reserves untapped is primarily a matter of getting the US to abstain, which is as plausible as electing a president like Bernie Sanders (who pledged to leave it in the ground). In a world dominated by multiple major powers you have a coordination problem: every power has a major incentive to not leave it in the ground unless all of the others agree to this as well. Gwynne Dyer, in Climate Wars, predicted how this would play out:

it was like the competition that raged between the Great Powers over the division of Africa in the thirty years before the First World War (even down to the detail that the prize wasn’t really worth the effort and the risk). But nuclear weapons kept everybody reasonably careful and, for the most part, it was just an enormous waste of money and time: warships confronting one another as drill rigs followed the retreating ice to the edge of the continental shelf and beyond, fishing vessels being arrested and confiscated, quarrels over Russian gas deliveries to Europe and a frantic European search for alternative sources of supply. The biggest short-term cost was the damage that the confrontation did to free-ish global trade, as the rivals issued ‘with me or against me’ ultimatums to smaller powers, forcing them to take sides. The long-term cost was the global deal on climate change, which had to wait more than a decade past its planned completion…because of the confrontation between the key players.

It is very unlikely that our ruling class will be able to solve this kind of coordination problem simply because of all of the incentives they have to not solve it. They are, after all, the most likely to benefit from things like competition over fossil fuels, and they are the least likely to be personally impacted by climate change.

I am personally not very optimistic about us escaping this trap, especially in time to prevent the worst effects of climate change — but if are to try, I can only see one way forward. Workers all over the world have to recognize their common interest in subordinating the bourgeoisie to an international body that has the power to do things like prohibit fossil fuel extraction in the arctic. If we can’t do that, Trump’s sabre rattling over Greenland will just be a small taste of what’s to come.

Refer enough friends to this site and you can read paywalled content for free!

And if you liked this post, why not share it?